- Home

- Sinan Antoon

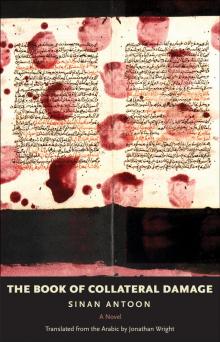

The Book of Collateral Damage

The Book of Collateral Damage Read online

The Book of Collateral Damage

The Book of Collateral Damage

SINAN ANTOON

TRANSLATED FROM THE ARABIC BY JONATHAN WRIGHT

YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW HAVEN & LONDON

The Margellos World Republic of Letters is dedicated to making literary works from around the globe available in English through translation. It brings to the English-speaking world the work of leading poets, novelists, essayists, philosophers, and playwrights from Europe, Latin America, Africa, Asia, and the Middle East to stimulate international discourse and creative exchange.

The author wishes to thank The Lannan Foundation for a residency in Marfa, Texas, in June 2014.

English translation copyright © 2019 by Jonathan Wright.

Published by arrangement with Rocking Chair Books Literary Agency and RAYA, the Agency for Arabic Literature.

Originally published in Arabic in 2016 as Fihris by Dar al-Jamal, Baghdad/Beirut.

Copyright © 2016 by Sinan Antoon.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Quotation from Jorge Luis Borges, “A New Refutation of Time,” from Selected Non-Fictions, edited by Eliot Weinberger, copyright © 1999 by Maria Kodama; translation copyright © 1999 by Penguin Random House LLC. Used by permission of Viking Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

Used by permission of The Wylie Agency LLC. All rights reserved.

Quotation from Jorge Luis Borges, “Cambridge,” translated by Hoyt Rogers, from Selected Poems, edited by Alexander Coleman, copyright © 1999 by Maria Kodama; translation copyright © 1999 by Hoyt Rogers. Used by permission of Viking Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail [email protected] (U.S. office) or [email protected] (U.K. office).

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018955516

ISBN 978-0-300-22894-6 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

He left many blank pages in it.

—On al-Fihris (The Index) by Ibn al-Nadim (d. 990)

They speak for the dead and translate the speech of the living.

—Al-Jahiz (d. 868), on books

Every passion borders on the chaotic, but the collector’s passion borders on the chaos of memories.

—Walter Benjamin

Time is the substance I am made of. Time is a river which sweeps me along, but I am the river. It is the tiger which destroys me, but I am the tiger; it is a fire which consumes me, but I am the fire.

—Jorge Luis Borges, A New Refutation of Time

We are our memory,

we are that chimerical museum of shifting shapes,

that pile of broken mirrors.

—Borges, Cambridge

Beginnings

THE COLLOQUY OF THE BIRDS

I can still remember the first time I flew.

“Come on. It’s time!” my father said firmly before flying off. My mother pushed me gently with her beak toward the edge and whispered, “Don’t be frightened, my little one. You’ll fly. We all fly. I’ll be right behind you.”

My three siblings were flying happily in the sky, oblivious to me. My heart was pounding, as if it, too, were also worried its wings might let it down. As if, like me, it was torn between the fear inside, which kept me in or close to the nest, and an overwhelming desire that compelled me to be like the grown-ups.

I moved forward warily to the tip of the branch, which dipped a little with my weight and that of my mother behind me. I didn’t look down. I looked up, where my father was circling in a clear, cloudless sky. I spread my wings, then looked back toward my mother. She didn’t say anything this time but her eyes gave me courage and she kissed my head with her beak. I remembered how she had often told me that we have strong wings and that mine would one day carry me to distant lands. I looked ahead and summoned all my courage and flapped my wings with vigor.

And I took off.

I couldn’t believe myself. I flew with confidence, as if I had often flown before. The cold air swept past my white feathers. The whole sky was mine and the whole earth was laid out below me. With a flip of a wing I could twist and turn, rise and fall. I kept flying till the sun bade us farewell. I was the last to return home that day.

I laugh now, and I’m embarrassed too, when I remember that moment and the fear that later left me. Here I am now, flying with the grown-ups for days on our journey to the warm lands.

A drop of sweat fell on the edge of the piece of paper and I stopped reading. His handwriting was neat and confident. The ink was black, maybe from a ballpoint pen. The words were perched like birds on lines that looked like small sky-blue threads running across small brown pages. I probably thought of this because he had written about the sky and flying. The passage reminded me of the storks’ nest I used to see in Shorja on the dome of a building when I was young. I turned the page. The title of the passage that followed also began with the word colloquy.

The air-conditioning unit in the room was panting and sputtering, and the pores of my skin were oozing sweat from the heat. I wiped the drop of sweat off the page with my finger and caught another one that was rolling down my forehead and about to drop. I left the pages on the bed next to the buff-colored notebook, stood up, went to the air-conditioning unit, and turned the dial counterclockwise as far as possible. I went to the bathroom and washed my face in cold water. I dried it with the towel and went back to stand in front of the air-conditioning unit for thirty seconds. I thought about the long, tiring journey to Amman. I had to pack and sleep a little, because we were scheduled to leave Baghdad at six a.m. I went back to the bed and read his letter a second time:

Dear Mr. al-Baghdadi,

I hope you had a productive day in the arms of your fatigued Baghdad. Apologies for intruding and daring to disturb you. But I’ve thought long and hard about the happy coincidence that brought us together and about your sincere interest in my project and your kind offer to translate it (although I’m not in a hurry to have it translated or even published, as I mentioned, at least not for now). I decided to take a risk and lay claim to more of your generosity and kindness. I sat down waiting for you at the hotel reception until half an hour before the start of the curfew so that I could deliver this part of the manuscript to you personally, but you didn’t come back. That’s why I’m writing this letter. I attach the first chapter (it’s the history of the first minute, which has yet to be completed, and I do have my own opinions on whether texts end or not and I might tell you about them in the future). I hope you like it and I hope you’ll give me your opinion with the candor and rigor of a critic and a writer, even if it is negative.

With this letter you’ll find a simple gift, because books are all I have in this world. I’ll try to obtain an email account so that we can communicate across the continents and the oceans. Thank you in advance and I apologize again if I was a little rude at the beginning of our meeting. I’m not usually much good at dealing with people and I prefer books, because they never hurt or betray.

With affection,

/> Your brother,

Wadood Abdulkarim,

Baghdad,

July 29, 2003

He’s not interested in being translated or published. So why is he sharing his manuscript with me so readily? Does he care that much what a stranger thinks? He’s strange, this Wadood. I folded the letter up and put it in the notebook I had bought specially to record my impressions during this visit. It had large pages that were slightly tan. The edges were stitched and trimmed unevenly to look like an old book. It had a thick cover of buff leather and a thin red ribbon attached to the top of the spine as a place marker. The marker was still on the first page, where I had written just one word since arriving: Baghdad.

I envied Wadood his productivity. I can’t even begin. And all this concern, or rather obsession, with writing rituals and instruments only ends in blank pages and silence. This visit had of course been hectic and hurried, and the pace of the work and daily travel exhausted me physically and mentally, leaving no time to write or even to think in peace. I have yet to start processing the whirl of scenes and people and ambivalent emotions. Nevertheless, I should have written something. One sentence at least. Every night I came back exhausted and sat on the bed. I picked up my pen but didn’t manage to write anything. The first night was the only night I wrote anything—that one word, Baghdad.

I went back to thinking about his manuscript and his gift, which wasn’t simple at all. Yes, it wasn’t the first edition, only the second, but it was the first part of the collected poems of Abbud al-Karkhi, and it does date back to 1956 and I think it’s rare. The book is in excellent condition. I browsed through the first few pages. There was a dedication to King Ghazi and a photograph of him on the next page, then one of al-Karkhi. The introduction was a collection of tributes and essays: there was a poem by al-Rusafi entitled “To the Poet of the Nation” (What a fine man you are, Abbud / With your rhymes you raise the banner of zajal), another poem by al-Zahawi, an essay by Raphael Butti on the use of colloquial Arabic in poetry and prose, one by al-Rusafi on zajal poetry and popular forms of literature, another one by Mohammad Bahjat al-Athari on colloquial and classical Arabic, and then, finally, the poems themselves. As I expected, “The Crusher,” al-Karkhi’s most famous poem, was the first in the collection. I fell asleep before I was halfway through and dreamed that al-Karkhi was our driver on the journey to Amman. All the way he recited his poems and explained their context and how they came about, but Roy kept insisting that I translate them. I lost my temper with him and said, “Poetry can’t be translated that way. We’re not at a press conference!” And I kept repeating, “One hour and I’ll break the crusher / And curse this damned life of mine.” Al-Karkhi roared with laughter and said, “How did you get stuck with them?”

I woke up to loud banging on the door of my room and Roy’s voice saying, “Come on, Nameer. We have to leave in half an hour. Don’t you want to eat breakfast?”

I had a shower in record time, dressed hurriedly, and stuffed the rest of my clothes and other things into my bag. I hadn’t bought anything other than the books from al-Mutanabbi Street. My bag was big enough for them and the box of cookies that my aunt had given me. I put Wadood’s envelope, my notebook, and the al-Karkhi poems in my backpack with my passport. I hate to be late for a departure or for any appointment, but I had another, much more important reason for hurrying. I wanted to savor one last time the Iraqi-style clotted cream and the hot sammun bread that arrived fresh every morning from a bakery close to the tiny hotel in Karrada. When I went down to the ground floor, Roy was going over the bill with the receptionist, who spoke enough English for them to understand each other, and I was already sick of translating. “Do you need any help?” I asked him anyway. “No, everything’s cool. You have some time because Laura’s still packing and needs twenty minutes. The driver hasn’t arrived yet either.”

I put my bag next to Roy’s big bag close to the front door and went to the hotel restaurant, a small room with four tables and a door that led to the kitchen. Abed, the waiter, saw me from inside the kitchen and we exchanged greetings. I sat down at a table on the right, turned my cup over, took a Lipton teabag from the plate in the middle of the table, and put it in the cup. If it had been real tea, from a teapot and flavored with cardamom, the breakfast would have been perfect. In America I had stopped drinking tea, especially after I moved out of my family’s house and switched to coffee. Two minutes later Abed arrived, carrying a tray with a small bowl of clotted cream, another with date syrup, and a blue plastic basket holding two loaves of sammun bread. He put the tray on the table in front of me, then went back to the kitchen to fetch the hot water for the tea. He hadn’t said much, except for the first day we had breakfast, a week earlier. He asked me at the time about my traveling companions.

“Excuse me, sir, but the group you’re with, what’s their story?” he said.

“They’re married and they’ve come to shoot a documentary,” I replied.

“Really? A month ago there was a group of French people staying here who were making a film too. Very well, and you would be the director?” he asked.

“No, I just came with them to translate for them and help them.”

“Do you live abroad?”

“Yes.”

“Where?”

“In the U.S.” I said.

“How long have you been away?”

“Since 1993.”

I asked him about his work.

“I’ve been working in this hotel for four years,” he replied. “Our house is in Camp Sarah but for the last few months, since the fall of Baghdad, I go there only once a week. I sleep here.”

We didn’t speak after that. He was always busy with his work, and over breakfast Roy, Laura, and I had discussed the day’s schedule and the places we were going to film. As he poured the hot water into the cup, he asked, “It looks like you’re leaving today, sir?”

“Yes, that’s right.”

“Hope you have a safe trip. Which city do you live in, sir?”

“In Boston,” I said. “But in one week I’m going to move to a state called New Hampshire,” I added for accuracy.

“I’ve never heard of it, to be honest.”

“It’s on the border with Canada. Very cold,” I said.

“The cold’s easier to take than this damned heat. What do you do there?”

“I’ve got a job at a university,” I replied.

“Congratulations. I hope it goes well.” I expected him to ask what my discipline was, but a voice called him from the kitchen. “Excuse me, sir,” he said politely.

I put two spoonsful of sugar in the cup of tea and stirred it. I took a sip that almost scorched my tongue and put the cup back. I took a loaf of sammun, split it open along the side, and spread the cream inside, adding two spoonsful of the date syrup. Abed didn’t come back. I ate slowly to enjoy my last breakfast. I had tasted this gaymar back in America on a visit to San Diego, where many Iraqis live, but it tasted different there. This cream reminded me of Umm Jalil’s cream, which she used to leave in a bowl on the stoop of our house early in the morning. I remembered how a stray cat rubbed its nose in the cream one morning and made off with some of it. Would Umm Jalil still be alive? I examined the sole painting hanging on the wall opposite. It was an attempt to draw a traditional Baghdadi backstreet. There were women in abayas carrying baskets with the dome of a mosque, a minaret, and a sunset scene in the background. The colors were garish and there were unintentional mistakes in the perspective and the proportions. An attempt to reproduce a sense of authenticity, but it fell into the trap of self-Orientalism. I reproached myself silently for the way I was overanalyzing. There I was—thinking like an academic even before I officially started my new job. I had seen many of these paintings in the city, sold to journalists and newcomers. I remembered that the department chair had asked me in an email to decide what course I planned to teach, apart from Arabic, so that it could be added to the curriculum, and I had to decide quickly.

The woman who had held the position before me had taught a class on Andalusian literature. The chair suggested I teach that too, and then I could propose another course for the following year. I didn’t have enough time to prepare a new course, and Andalusian literature would be an opportunity to reduce the number of questions on terrorism and jihad, which had intruded on every class and lecture since 9/11.

I began the rituals of preparing another piece of sammun and cream, but Roy’s voice called from the reception. “Hey, Nameer. Laura’s ready and the driver’s waiting.” I finished making the sandwich, wrapped it in a paper napkin that was on the table, put it in one of the pockets of my backpack, and drank the cup of tea, which wasn’t quite so hot.

Mullah Abbud al-Karkhi wasn’t in the driver’s seat, just Abularif, the Jordanian driver who had been with us throughout the visit and who worked on the Amman-Baghdad route and knew Baghdad well. Roy and Laura sat in the front seat next to the driver, while I took the back seat so I could stretch out and sleep.

Baghdad was still sleepy and yawning. Most of the shops had their eyes shut. There were some people on the sidewalks, but the streets were semideserted. A car drove past us from time to time. American tanks and armored vehicles were lurking at the junctions. Someone had written “US Army Go Home” in red paint on a wall. I was the one going back to the country that the U.S. Army came from, while it looked likely to stay. I was going back to a country that was not yet “home” even after a full decade. I had read expressions of gratitude to the Americans on other walls that made me sad. I wanted to see the Tigris and say goodbye to it. I didn’t know when I would come back, or whether I ever would. The Tigris looked so pale on this visit. It no longer looked the way I remembered it. But did anything still look the way I remembered? Nothing had managed to escape turning pale. A pigeon fancier had awakened early to let out his flock and watch the pigeons circle in the city sky. Seeing the birds in flight suggested an answer to my question—an answer that gave wing to a simple joy. The doves were still as they were—beautiful and free … free at least for this fleeting moment.

The Book of Collateral Damage

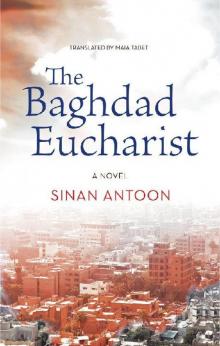

The Book of Collateral Damage The Baghdad Eucharist

The Baghdad Eucharist