- Home

- Sinan Antoon

The Book of Collateral Damage Page 2

The Book of Collateral Damage Read online

Page 2

The doves reminded me of the stork in Wadood’s manuscript. I thought about him coming to the hotel and leaving his manuscript for me. It struck me as a rather strange and impulsive gesture. Or was I exaggerating and being too hard on him? Hadn’t I asked him to write to me? Hadn’t I offered to help? My sudden return to Baghdad with these Americans was also strange and impulsive. Had I come to rediscover something, or to make sure it was lost? Wasn’t I ill at ease in this city and in a hurry to leave? Had I come back to examine the wounds I had left behind, or what? I wanted to read the rest of the manuscript, but not now because I was exhausted and sleepy. Later. It was a long way to Amman.

I woke up after about two hours to find desert stretching away on both sides of the road. I asked the driver where we were. “We passed Ramadi an hour ago. The others are sleeping too.” I looked at them. Laura’s head was in Roy’s arms, and his was resting on the small bag that he used as a pillow.

“Didn’t they stop us along the way?” I asked.

“No,” he said, “only at the first checkpoint at Abu Ghraib.”

“How long to the border?” I asked.

“You’ve got al-Rutba in an hour and a half and then about an hour after that we get to the border.” He paused and then, looking at me in the big rearview mirror and half smiling, he added, “What? You’re in a hurry to get out of Iraq, Mr. Nameer?”

He took every opportunity to make bad-tempered and malicious remarks. Twice I had argued with him angrily and I raised my voice so loud that I upset Roy. On one occasion I had confronted him, saying, “You love Saddam.”

He was evasive, saying, “No, but I’m not with the Americans.”

“And what makes you think I’m with the Americans?” I replied, but then I decided there was nothing to be gained by arguing with him. “No, Abularif,” I said. “That’s unfair. Did you ever have a passenger who didn’t ask where we are and when we’ll arrive?”

“Just joking,” he laughed.

I was going to tell him that I missed being myself and on my own. I was tired of translating everything that was said. I had spent six whole days with them: Roy, Laura, and Abularif too. From early morning to sunset we had gone everywhere conducting interviews and filming. They were pleasant and working with them was easy, but six days was enough. The day before had been the only day when I was able to breathe and move around freely. Abularif took them to al-Nahr Street and the copperworkers’ market to buy gifts, walk around the markets, and then have some traditional grilled fish to eat. I had gone to al-Mutanabbi Street to wander around and buy books. After that I went to our old house and then my aunt’s, who had prepared a meal of stuffed grape leaves for me and invited relatives for me to meet. She pressed me to invite “your American friends that you’re filming with,” but I told her I preferred to come alone.

“They don’t speak Arabic, auntie,” I said, “and if they come I’ll have to keep translating for them and I won’t be able to enjoy being with you. Besides, they’re busy tomorrow.”

“As you wish then. Okay, do you remember our house? Can you find the way on your own?”

“Of course I can, what do you mean?” I said.

I used to go there as a child in the summer and play with my cousins and sleep there days at a time.

I walked a little, then took a taxi from al-Rusafi Square to our house in al-Amin al-Ula, which was later changed to al-Khaleej. I wanted to take a look at it and say hello to any of our neighbors who were still there. When we were about to approach the al-Amin bridge, I asked the driver not to cross to the other side of the canal because the street that led to the house was directly on the right. The cars slowed down and we saw a traffic jam in front of the street that led to our neighborhood. Some of the cars were turning and driving back toward us in the opposite direction. There were some Hummers and American troops waving the cars back. The driver wound down the window and shouted at one of the drivers who were coming back.

“What’s going on?”

“The street’s blocked,” the other driver replied, “and they’re not letting anyone in.”

He looked at me with a sigh.

“I know another way,” I said. “We can go back and get in near the courthouse and through the backstreets.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yes.”

He turned the car around and we went back. We turned at the traffic circle and took one of the streets leading to our street, but then we saw a Hummer parked at the end of the street. There was a man standing outside his house with a child and I asked him what was going on.

“They’ve been sealing off the area for an hour,” he said.

I thought of getting out of the taxi and walking.

“Are they letting pedestrians through?” I asked him.

He shook his head and said, “No. No pedestrians and no vehicles.”

The driver was looking at me and expecting me to pay the fare, so I asked him, “Can you take me to Beirut Square?” and he agreed.

I felt a lump in the throat. I had wanted to have a look at the house and the street I had played and run around in. I had thought I would knock on the neighbors’ doors and ask about my childhood friends. The taxi driver didn’t speak throughout the ride.

I wiped my sweat away with a handkerchief I was carrying after he dropped me off in front of my aunt’s house. I saw three cars parked on the pavement. I pressed the bell outside, then pushed the metal gate, which was a little rusty and had flaking white paint. The garden wasn’t as lush as it used to be. My aunt’s husband, who had died three or four years earlier, had treated the garden as sacred ground. I noticed they had added some rooms to the second floor. There was a separate entrance with a staircase. My aunt came out through the front door and started ululating. Her face was still the same, except for the wrinkles. But most of her hair had disappeared beneath a black hijab that she hadn’t worn before I left Baghdad. Wiam, her eldest son, came out behind her. I later learned that he and his wife and children were the ones living on the second floor. She cried as she hugged and kissed me, and started to scold me, of course.

“Shame on you. You’ve been here a whole week and you only come on the last day,” she said. “We haven’t seen you for ten years. Don’t you love your auntie any longer, you rascal?” “The man’s a doctor now and you still call him a rascal?” Wiam told her. I gave him a kiss and said, “I’m not a doctor yet. My dissertation isn’t finished yet.” He laughed and said, “All but a doctor.” The others were waiting inside: my cousins, my other uncle and his wife, and their children and their wives and children. I greeted them one by one and tried to remember the names of the children and the people I hadn’t met before. As for the grown-ups I had known before, time seemed to have crushed them like a steamroller, as if they had had to live through the last ten years several times over, back and forth, and had endured massive doses of pain.

“Why don’t you stay here with us for a few days, my dear?” my aunt asked me as soon as I sat down.

“Unfortunately, I have to go back to Amman tomorrow.”

“You mean you couldn’t put off traveling for a few days?”

“No, auntie, I have to go back. I have a stack of responsibilities. I have to move to a new state and get ready to teach.”

When I had called her to tell her I was in Baghdad, she had wanted me to leave the hotel and stay at her house. “It’s a shame to come to Baghdad and stay in a hotel. Bring your American friends to stay at our place. We can make room for them. Bring them over,” she said.

I told her that the filming schedule wouldn’t allow it and they had to charge the batteries for their equipment every night and so we had to be in a place where there were no power cuts. “We have a generator, dear,” she said.

My uncle, a retired engineer, was the only one to ask about my dissertation and the academic work I was about to start. The others bombarded me with questions about America and life there and what would happen in Iraq in the future, as if I knew

or were in direct contact with Bush. Like the people whose words I had translated on camera for the past six days, my relatives were divided over what had happened. There was no consensus, even on the right term to use: occupation or liberation. There was an acrimonious argument between the men while my aunt supervised the preparation of the table. One of my cousins turned to me to ask me what I thought. He didn’t like what I said and asked, “So you came out too to protest against the war?”

“Of course,” I said.

He laughed and said sarcastically, “You are so spoiled, man. If you’d been living here with us all these years, even if the Angel of Death had come to liberate you, you would have welcomed him.”

“America is the official agent of the Angel of Death,” I said.

“Oh really! So why do you live there?” he asked in a loud voice.

“Enough,” his father rebuked him, “you’ve gone too far!”

My aunt called from the guest room, “That’s enough arguing. Come and eat.”

I asked her about the tablets I’d seen her putting in the water jug. She told me it was to sterilize the water because otherwise it would cause diarrhea. She put plenty of dolma on my plate, especially stuffed onions because she knew how much I loved them. Then she said, “Is there food like this in America?”

“Where I live there aren’t any Iraqi restaurants,” I said.

“You’ve been living as a bachelor all these years, so why haven’t you learned to cook?” she asked.

“Sometimes I cook, but not dolma.”

After lunch we went back to the living room. I felt quite exhausted and could hardly keep my eyes open, but I pretended to follow the discussion against a background of clinking teacups and the sound of drinking. My aunt saved me by suggesting I take a siesta on the sofa in the guest room under the opening of the aircooler “where you used to sleep in summer when you came here, remember?”

I smiled. “Of course I remember. Yes, please.”

I took off my shoes and socks, put my head on the pillow she brought, and slept for an hour and a half. Then I woke up, washed my face, and went back to the living room. We chatted at length and drank tea again with the klaicha cookies that my aunt had made specially for me. She gave me a full box of them to take with me.

Before I said goodbye to them, my aunt pulled me by the arm and asked to speak to me alone. When she was alone with me she told me off for cutting off my father and not speaking to him for years. I asked her whether she knew the reason, what he had done to my mother.

“It doesn’t matter,” she said. “Whatever happened, he’s still your father. Be magnanimous and don’t break his heart. For my sake, Nameer. When you get back, speak to him. Please.”

I didn’t want to disappoint her so I promised to think about it. That was a white lie, like my promise that I would soon come back for a longer visit without work or other commitments. She made sure she sprinkled water after me so that I would come back. My cousin Midhat drove me to the hotel and gave me his phone number and email address before we said goodbye. The outer gate was locked, but the guard recognized me and opened it for me. I greeted the receptionist, who was watching television in the room next to the front desk.

“My friend,” he shouted, “there’s a package for you.”

He got up from his chair, came to the reception desk, bent down looking for something, and then handed me a brown envelope. “Your friend Wadood,” he said. “He waited here an hour and a half, and then he went, but asked me to pass this on to you.”

I was surprised. I thanked him, took the envelope, and went up to my room.

Preamble (draft)

How can I write what happened?

(This “how” kept me up at night for many years.) And how can what I write escape the traps of distortion and domination of official history? I realize there’s something paradoxical and ironic about it. Is it reasonable to worry about the fate of what I write before my pen even begins to bleed ink onto paper? There’s a wonderful African proverb in Chinua Achebe’s novel Things Fall Apart that goes “Until lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.” The idea isn’t new, of course, but the metaphor is a gem. The victors are always the ones who write history. By the time someone who wants to revise, question, or change it comes along, it’s already too late. But what about the history of the victim? Or the victim’s victim? That’s what I am concerned with. The first time I read that proverb I empathized with the lion, of course. But then I thought hard about the matter and reconsidered, to discover, or rather remember, that I should be in solidarity with the lion’s victim. I imagined, even felt, that I was inhabiting the gazelle (or any other prey) in this equation because it represents me and I represent it. I even feel I am it. I am the one who’s been marginalized and disappeared at least twice. I’m the prey’s prey. As for numbers, they don’t serve the purpose. Statistics may count us, but at best they diminish our lives and our deaths. They dehumanize us. Assuming there’s someone to count in the first place, because the historians of the hunt count the number of dead hunters! Numbers turn us into numbers. Dead signs and symbols in comparative studies designed to improve the hunt and make it more efficient. Our details disappear—our features, our color, our voices, our memories, our skin, our eyes, and so on. Once we’ve been skinned, our skins might be tanned and hung on the wall in the hunters’ homes. Or photographs of the hunters, standing next to our dead bodies to celebrate a new record, might be hung on museum walls.

But where should I begin, and how? Can I enter time through a hole or through the window of one moment in time? I believe so. As soon as I get inside time, I can take the moment and analyze it as if it’s a tear or a drop of blood under the microscope and discover the bonds and interactions that produce it. But how can I describe the moment when it isn’t a moment, but in fact more like a tree? So I have to get down to the roots and listen to the earth’s conversation with the tree and what it drinks from the earth. Then there’s the trunk and everyone who has ever leaned on it or carved their name on it. And the branches and their memory and everything the wind has picked up and scattered far and wide. And all the birds that have perched on it on their way to distant places. And the ones that have nested in it and so on. It’s a labyrinth. And which particular moment are we talking about? Is the moment the same moment everywhere? Or is each moment associated with its own place in the universe? If this last possibility is the case, then there is more than one time. There are times that might intersect but never coincide. But in this project I’m interested in one time in one place. First, I’ll write down the history of the first minute of the war, which wasn’t the first war I’ve seen. Most of the people who tackle history record centuries, decades, and years. I’m interested in minutes, especially the first minute.

The minute will be a three-dimensional space. It will be a place where I snipe at things and souls as they move. The juncture where they meet before disappearing forever, without saying goodbye. Humans say goodbye only to those they know and those they love, whereas things say goodbye to each other and to humans too. But we rarely hear their voices, their whispers, because we don’t try. We rarely notice things smiling. Yes, things have faces too, but we don’t see them. Those who do see them, after making an effort and training themselves to do so, and those who talk to them are labeled mad by your standards.

I’m the one who saw everything, and I see what they don’t see.

There’s always a moment in the life of every being and every thing in which their whole truth is manifested. A moment when the past intersects with the future. Those who can see and hear can discern the truth about that being. You no doubt sometimes see a photograph of a famous person, or even an ordinary person. And you realize that this photograph/moment preserves the whole existence and history of that person. I’m not sure, but many of these condensed moments come just before death. I know I contradict myself sometimes. Is there any way around that?

T

ime is a black hole. A hole into which things fall and disappear. Even the beginning of this whole universe, according to one theory, was an explosion. And the universe is just fragments and debris, and here we are, living the consequences and effects of it. I’m going to pluck this minute out of the black hole. But why? There are people who write in order to change the present or the future, whereas I dream of changing the past. This is my rationale and the rationale of my catalog.

I liked the preamble, the idea of a history of the prey and a catalog of the first minute. These were wild ideas that were not afraid to take risks. He could elaborate further of course and set his mind to arranging the sequence of ideas. I jotted down some notes in my notebook. I kept reading as we waited at the Iraqi border post at Traibil and again as we waited at al-Karama on the Jordanian side. I thought of writing about Wadood and his project. It could be intertextual with his catalog, including excerpts from it. Why not? But I had to find out more about his background and his life. I scolded myself for getting carried away with an idea that was wonderful but totally impractical. (Are wonderful things ever practical?) I had to finish my doctoral dissertation to secure my job, and I had to turn it into an academic work, and after that I might be free for novels. That would be logical, but it’s not my logic.

Abularif drove me to the airport because my flight was due to take off in three hours. Roy and Laura planned to stay in Amman and visit Petra and Wadi Rum. “We need a holiday after all that pressure. It was so intense,” said Laura, who overused the word intense, often for things that didn’t deserve to be described as such. We hugged and I thanked them for the opportunity they had given me and reminded them that my offer to help them translate the film when it was finished still stood.

I don’t know what came over me when I agreed to go to Baghdad after all those years. It would have been better to go alone. At least to ensure that I had freedom of movement and could choose what I wanted to see, instead of being hostage to the team and its schedule, to which I was committed. But what was the point of all these recriminations now? There wouldn’t be another trip. I had gone without expectations and thought I had immunized myself against any additional disappointments. I had read a great deal about what happens to emigrants who go back after a long absence and, consciously or not, search for what is left. I had read about selective memory and nostalgia and its snares. But the texts didn’t help much.

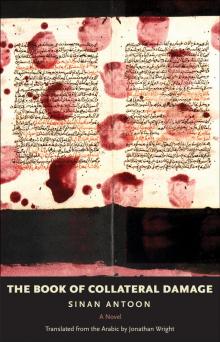

The Book of Collateral Damage

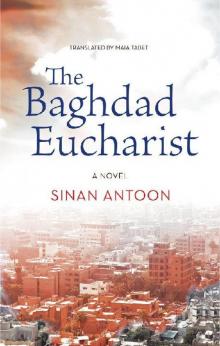

The Book of Collateral Damage The Baghdad Eucharist

The Baghdad Eucharist